“My own butt was the inspiration for all of this,” said Sara Blakely, founder of Spanx, an entrepreneurial firm in the shapewear industry with an estimated market value of $1 billion (Wolfe, 2013). Sara is both a surprised and a surprising role model for growth-oriented women entrepreneurs. As the daughter of an attorney, she attended Florida State University with the goal of becoming a lawyer like her father. Low scores on the LSAT derailed her plan, however, and she ended up selling fax machines. Long hours on the road gave her time to fantasize about creating a product that she could sell and others would be willing to buy. Consistent with her vision, she founded Spanx at the age of twenty-seven. Originally, Spanx produced a lower body shaper for women that filled the gap between the girdles of yesteryear and the much more sheer women’s underwear of today. The product’s appeal is that it allows women to feel more confident by smoothing out bulges and bumps, while remaining relatively comfortable. Endorsements from Oprah Winfrey helped launch Spanx in 2000, and the following year, Sara started selling her products on QVC, the home shopping channel. Spanx were and continue to be sold in department stores where Sara has marketed the product using “before” and “after” photos of her derriere. After the success of her initial product line, Sara branched out into additional offerings including denim leggings, swimwear, workout clothing, and men’s Spanx. In 2013, Sara was the first woman to join Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge by agreeing to donate over half of her wealth to charity. Today, Sara remains the sole owner of Spanx, which had sales of almost $700 million in 2013.

We could not resist Sara Blakely’s story as a way to launch our own entrepreneurial venture, a book that focuses on the financing strategies of growth-oriented, women-owned firms. Sara is part of a new and growing vanguard of women who are taking the plunge and growing their firms to achieve significant size and scope. For these women, the sky’s the limit, and they are paving the way for those who follow. Although today only a small percentage of women own firms with revenues in excess of $1 million, entrepreneurs like Sara Blakely are breaking new ground, developing market-driven products and services, and designing strategies to achieve success on their own terms. This book is a celebration of their accomplishments, as well as an examination of the financial strategies that have helped them succeed.

Before we delve into the details, however, let’s start with some preliminary questions: Why growth? Why women entrepreneurs? Why now? Traditionally, women-owned firms in the United States have been small. Even today, the vast majority of women-owned firms have no employees aside from the entrepreneur herself (2012 Survey of Business Owners). Similarly, women-owned firms have been “small” in terms of revenues. Thus, women-owned enterprises have typically been low-growth or no-growth “lifestyle” firms, often home-based and concentrated in service and retail sectors. A primary motivation for women entrepreneurs like these has been the desire to supplement family income in ways that allow them to be at home with children while they are young. We featured one such entrepreneur, Debbie Gadowsky, the founder of Cookies Direct, in our first book, A Rising Tide: Financing Strategies for Women-Owned Firms (Coleman and Robb, 2012). Debbie initially launched her firm at home with the goal of helping to finance college educations for her two children. She has done that and more, and now ships cookie baskets all over the world, achieving revenues of $500,000 per year while still operating out of her home.

More recently, however, a new cohort of women entrepreneurs has emerged. Unlike Debbie, who launched with the specific goal of establishing a relatively small and manageable home-based firm, these women start their firms with the intent to achieve significant size and scale. In this sense, they are a “new breed” that has emerged from the economic, social, and cultural characteristics of our time. Sara Blakely typifies entrepreneurs of this type in that she is young, well educated, creative, and visionary. She is also motivated not only by the innovative nature of her products but also by the economic rewards that they provide to her as an entrepreneur. Further, she values recognition as well as the opportunity to make an impact at a national or even international level. As a way to begin answering our questions Why growth? Why women? and Why now? let’s examine the factors that have “made” Sara Blakely as well as other growth-oriented women entrepreneurs like her.

Economic Impacts of Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship

Every year, thousands of firms are launched, and simultaneously thousands of standing firms die or cease to exist through a variety of means. This pattern illustrates economist and political scientist Joseph Schumpeter’s theme of “creative destruction,” which is at the heart of the entrepreneurial process (Schumpeter, 1934). In the United States, the vast majority of firms are young and small. Some of these firms will grow into large enterprises, but most of those that manage to survive the first few years will remain small. The U.S. Small Business Administration defines a “small business” as a firm having five hundred or fewer employees, and 99 percent of all firms in this country fall into that category. In fact, most of these firms are “very small,” with ten or fewer employees and annual revenues of $100,000 or less (Lowrey, 2011). Nevertheless, the firms that we continually hear about in the business press are the big ones.

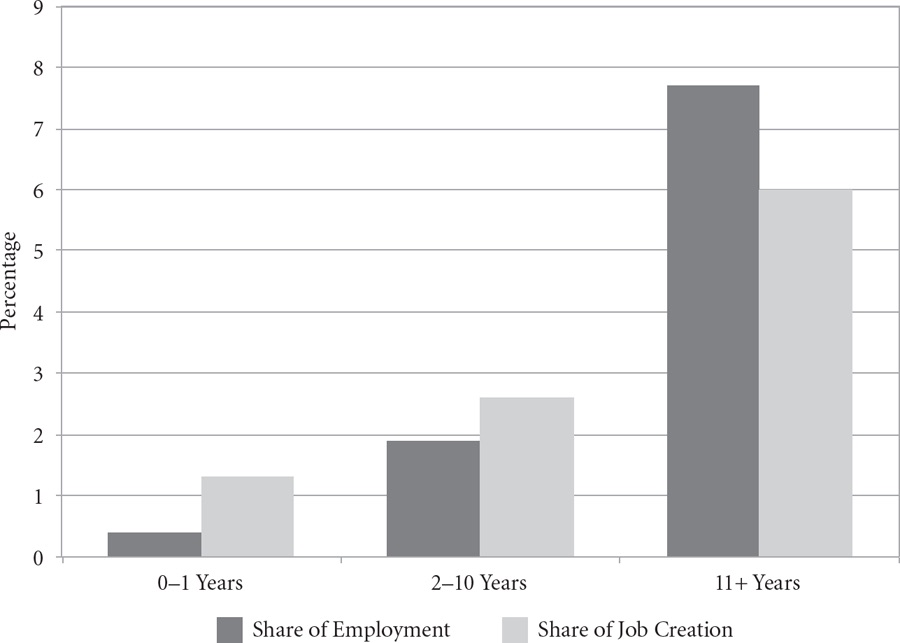

Why are we so focused on this small percentage of very large firms? Our preoccupation with growth-oriented firms can be explained by two major considerations: their ability to contribute to economic growth and their potential for creating a significant number of new jobs (Haltiwanger, Miranda, and Jarmin, 2013; Audretsch, 2007; Wennekers and Thurik, 1999). Prior research reveals that young, growth-oriented entrepreneurial ventures disproportionately create jobs in the United States (Haltiwanger, Hyatt, McEntarfer, and Soufa, 2012; Haltiwanger, Jarmin, and Miranda, 2010). While firms under ten years of age only account for about 25 percent of overall employment, they account for about 40 percent of job creation (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1. Share of Employment and Job Creation by Firm Age

Source: Kauffman Foundation BDS Statistics Briefing (Haltiwanger and others, 2012)

The job creation potential of new growth-oriented firms is particularly important now. Although the United States has emerged from a global financial crisis and the worst recession in eighty years, the job market continues to pose challenges. The current national unemployment rate is 5.5 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015a). However, this national percentage masks the stark nature of the job market for some segments of the population. As examples, the unemployment rate for young people, those in the twenty-to-twenty-four-year age range, is 10.6 percent, and for those in the eighteen-to-nineteen-year age range it’s 16.8 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015b). For black and Hispanic young adults, the rate is even higher. This age range is the point at which young adults typically launch their careers, get married, buy cars and houses, and start families. Their inability to find jobs postpones that entire process and reduces the likelihood of positive outcomes.

These factors help us in answering the questions Why growth? and Why now? However, our third question, Why women?, remains. Several scholars have pointed out that women entrepreneurs represent an economic resource that has yet to be fully tapped. Although women represent roughly 50 percent of the population, they represent only about one-third of entrepreneurs (Minnitti, 2010; 2012 Survey of Business Owners). The “gender gap” in growth-oriented entrepreneurship is even wider. A recent report from the Kauffman Foundation points out,

With nearly half of the workforce and more than half of our college students now being women, their lag in building high-growth firms has become a major economic deficit. The nation has fewer jobs—and less strength in emerging industries—than it could if women’s entrepreneurship were on a par with men’s. Women capable of starting growth companies may well be our greatest under-utilized economic resource. (Mitchell, 2011, p. 2)

In spite of this persistent gap between men and women in the level of growth-oriented entrepreneurship, a number of factors are contributing to positive change. Some of these factors represent changing trends in education, society, and culture, while others represent motivational drivers that are prompting more women to take the plunge. Taken together, these various factors have contributed to a changing entrepreneurial landscape and a blurring of many boundaries that have traditionally separated the types of firms that women launch from those launched by men. Let’s take a few moments to review some of these changes.

Educational, Social, and Cultural Factors

Today’s women entrepreneurs are better educated, better trained, and better prepared than ever before. From the standpoint of education, the number of women graduating from college actually exceeds the number of men. Although men are still more likely to have graduate degrees, women are gaining rapidly. Thanks to initiatives at the local, state, and federal levels, women are also diversifying their fields of study to encompass previously male-dominated disciplines such as science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) (Landivar, 2013). These academic disciplines are important because they often serve as a gateway for entry into fields such as health care, information technology, and manufacturing, all of which are fertile ground for innovation and entrepreneurship. Continued progress in this area will help to break down the “industry segregation” that has constrained women to service and retail fields, which are highly competitive, less growth-oriented, and less profitable (Hudson, 2006; Wang, 2013).

In addition to these educational gains and the new opportunities they unlock for women entrepreneurs, a major social and cultural change has been the number of women who work outside of the home. Working women are not necessarily a new phenomenon, but a growing number of these women are now holding positions of influence and power in both large and small corporations (2012 Catalyst Census). These positions help women develop skills in a broad range of areas, including the ability to manage others, the ability to make important and often difficult decisions, and the ability to see the “big picture.” Taken together, these educational and workplace changes have helped to equip a growing number of women with the human capital required to launch growth-oriented firms.

In spite of these changes, however, women still face challenges in corporate environments. Although women are now well represented in middle management positions, few have reached the executive suite or board of directors level (Ding, Murray, and Stuart, 2013; Nelson and Levesque, 2007). Studies conducted by Catalyst, an organization devoted to expanding opportunities for women, found that women held only 4.2 percent of the CEO positions in Fortune 500 firms in 2012. Similarly, women held only 16.6 percent of the board seats for these firms (Missing Pieces, 2013). In a study on the development of “high potentials” capable of serving on boards for both public and private companies, the authors noted that

men are more likely than women to have career experiences managing people, being responsible for profit functions, and attaining executive status in their current jobs. (Carter and others, 2013, p. 6)

A number of the women entrepreneurs we have spoken with allude to the “glass ceiling,” which prevented them from advancing to the most senior ranks of their former firms—creating an impetus to start their own. From a public policy perspective, one of our challenges going forward is to ensure that women have advancement opportunities in their firms and organizations. As in the case of educational and experiential gains, these types of leadership opportunities will help to equip them with the skills needed to launch growth-oriented firms.

Financial Rewards as a Motivator: Oprah Winfrey

In addition to basic advancement, an important motivator for growth-oriented entrepreneurs, both male and female, is the potential for significant financial and economic gains. Consider the case of Oprah Winfrey, who is not only a highly successful growth-oriented entrepreneur, but also one of the wealthiest individuals in the United States.

Oprah Winfrey was born to a teenage single mother in rural Mississippi. Raised in an inner city neighborhood in Milwaukee, Winfrey was sexually abused by family members and friends of her mother as a child. She became pregnant at the age of fourteen, and gave birth to a son who later died. Oprah subsequently moved to Nashville, Tennessee, to live with her father. While there, she enrolled in Tennessee State University and began working in local radio and TV in 1971. After graduating from college, Winfrey embarked on her broadcasting career in earnest, hosting her first television chat show in 1976. This led to the launch of the now famous Oprah Winfrey Show as a nationally syndicated program in 1986. Winfrey launched her own production company, Harpo (Oprah spelled backward) to house the show, which became increasingly popular and increasingly profitable. Her show focused on issues and topics that resonate with women, highlighting both the joys and challenges of everyday life. Simultaneously, she addressed difficult topics such as sexual abuse, sexual preference, substance abuse, and marital fidelity. When the trend toward “trashy talk shows” emerged in the 1990s, Winfrey bucked it and signaled her respect for her audience by avoiding tawdry topics. In contrast, she focused increasingly on topics relating to self-improvement, strategies for overcoming adversity, and spirituality.

Winfrey went on to launch additional entrepreneurial initiatives, including Oprah’s Book Club, O: the Oprah Magazine, Oxygen Media, and the Oprah Winfrey Network. As a role model and thought leader, Oprah has inspired many women to take control of their destinies by getting out of bad relationships, taking charge of their emotional and physical well-being, and improving their lives. For almost three decades, she has served as an enduring example of courage, dignity, common sense, and spunk. In 2013, Oprah Winfrey had a net worth of $2.9 billion and held the distinction of being America’s only African-American billionaire. In addition to the many accolades and awards that she has received in her field, including numerous Emmys and a Lifetime Achievement Award by the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, Winfrey has been recognized as a member of the Forbes 400, a listing of the four hundred wealthiest individuals in the United States (http://www.forbes.com). In 2013, Forbes also recognized Winfrey as number 13 on its list of the world’s most powerful women.1 While women like Oprah show the earning potential of a high-growth women entrepreneur, traditionally, women’s earnings have lagged those of men. This persists even today.

Recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that full-time women workers’ earnings are only about 81 percent of that of their male counterparts. The pay gap is even greater for African-American and Latina women, with African-American women earning 64 cents and Latina women earning 56 cents for every dollar earned by a Caucasian man (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013). A number of reasons have been put forth for this discrepancy, including the fact that women are more likely to have career interruptions associated with the birth of children or their subsequent care in the home. Further, as noted above, many women have gravitated to fields that simply do not pay as well as others, such as teaching, nursing, and clerical work versus manufacturing, computer science, and engineering. These boundaries are shifting, however, as more women assume the role of primary wage earner for their families. A record 40 percent of all households with children under the age of eighteen include mothers who are either the sole or primary source of income for the family, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The share was just 11 percent in 19602 (Wang, Parker, and Taylor, 2013). Similarly, women are now well represented in a number of previously male-dominated fields such as medicine, accounting, and law. These factors have raised women’s aspirations and expectations for higher earnings and opportunities for career advancement.

Being Recognized as a Leader

Another motivator for growth-oriented women entrepreneurs is the opportunity for recognition as a leader in their field at either a national or even an international level. Beyond the firm, leadership roles allow women to shape the direction of their industries and provide input on key issues such as legislation, regulations, and public policy, all of which will have an impact on them. Like well-known male entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates or Steve Jobs, women entrepreneurs want to be recognized as “movers and shakers.” They want to be taken seriously, and they believe they have earned that right. This is a motivator that surfaced in our first book, A Rising Tide, as several of the women entrepreneurs that we interviewed spoke of their desire to reach their full potential and to be respected, valued, and looked up to for their accomplishments. They wanted to validate their own capabilities and talent through their entrepreneurial ventures, but they wanted external validation as well.

These themes are especially prominent in women entrepreneurs who aspire to growth. Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw established her biotech firm, Biogen, in Bangalore, India, in 1978, operating out of her garage and starting with the equivalent of approximately $200 in funding (Anderson, 2012). In 2004, Biogen went public with a market value of over $1 billion and now operates on a global scale. One of Mazumdar-Shaw’s goals has been to make health care more affordable and more accessible, particularly for the poor. In a 2012 interview with CNN she stated,

India is a country where 80% of healthcare is out of pocket; where 80% of healthcare infrastructure is in the private sector; where most people don’t have access to quality healthcare (Anderson, 2012).

In the face of these grim statistics, Mazumdar-Shaw resolved to be an agent of change by using technology to bring down the cost of developing new drugs. She has earned global acclaim and was recognized as a Technology Pioneer by the World Economic Forum. She has also received national awards presented by the president of India for her pioneering work in the field of biotechnology. (http://www.biocon.com)

Making an Impact

Each of the growth-oriented women entrepreneurs we have referenced—Sara Blakely, Oprah Winfrey, and Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw—has sought ways to have an impact beyond the boundaries of her company. Each of our entrepreneurs has used her wealth and influence to address issues and causes on a larger scale. As noted, Sara Blakely has made a commitment to donate half of her wealth to charity. Her efforts to date have been focused on initiatives that help women and girls. One such project was the Empowerment Plan, a Detroit-based program that works to create jobs for homeless women (Spanx Mogul Sara Blakely Becomes First Female Billionaire to Join Gates-Buffett Giving Pledge, 2013). Her pledge letter states,

Since I was a little girl I have always known I would help women. In my wildest dreams I never thought I would have started with their butts. As it turns out, that was a great place to start! At Spanx we say it’s our goal to make the world a better place, one butt at a time. With this pledge my goal is to make the world a better place . . . one woman at a time. (http://www.givingpledge.org)

Oprah Winfrey has provided generous financial support to a broad range of individuals and causes. One of the initiatives that has been most important to her is the Leadership Academy for Girls located in South Africa, which Winfrey established in 2002 and has been funding ever since (The Education of Oprah Winfrey, 2012). Beyond that, her visibility as a celebrity has enabled her to take positions of social and political issues. As an example, in the 2008 presidential campaign Winfrey was an outspoken supporter of then little-known candidate Barack Obama. Her support is credited with persuading roughly one million voters to support Obama in a race that led to the election of America’s first black president. (McClatchy, 2007)

In addition to her desire to lower the costs associated with developing new drugs, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw wanted to start a firm that would help to arrest the “brain drain” of bright young scientists from India to other nations. Today her firm employs almost five thousand scientists, including a significant number of women who were previously sidelined and bypassed for the most desirable jobs in science and technology fields (Anderson, 2012). These examples highlight our belief that growth-oriented women often have societal goals and aspirations driving their choices. The fact that they have been so successful in launching and growing their firms provides them with a platform for addressing other issues and causes for which they have a passion.

Growth-Oriented Women Entrepreneurs as Role Models

Women entrepreneurs who have successfully grown their firms can also have an impact by serving as role models and mentors for other women contemplating entrepreneurship or attempting to launch their businesses. This is particularly important given the continuing gap between the numbers of women- and men-owned firms. This gap is even more pronounced for growth-oriented firms. Women such as Sara Blakely, Oprah Winfrey, and Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw serve as an inspiration for the thousands of women who dream of following in their footsteps. Each of these remarkable women has also taken it upon herself to help other women and girls reach their educational, career, or entrepreneurial goals. In A Rising Tide one of our key strategies for women entrepreneurs was to “pay it forward” (Coleman and Robb, 2012, p. 244). We advised aspiring women entrepreneurs to get mentors, and we urged successful women entrepreneurs to be mentors. These measures are all a part of the “rising tide” of women’s entrepreneurship that we addressed in that book. In order for women entrepreneurs to succeed, they have to help and support each other. In other words, women’s entrepreneurship is not a zero sum game in which some women can succeed only if others fail. In contrast, entrepreneurship is a “big boat,” and there is plenty of room for more talented, energetic, and determined women like those we have described in this chapter. In The Next Wave, we will highlight the importance and impact of successful women entrepreneurs on the launch and development of other growth-oriented women-owned ventures.

Growth-Oriented Women Entrepreneurs as Investors

One of the newest and most exciting ways in which successful women can have an impact is by investing in other emerging entrepreneurs. Many of these investors are professional women such as attorneys, doctors, and accountants, but a growing number are women entrepreneurs who have launched their own successful growth-oriented firms. In recognition of this trend, organizations such as Springboard Enterprises, Astia, Pipeline Angels, and Golden Seeds provide both training and opportunities for women to invest. For example, Golden Seeds has established a “Knowledge Institute” to train and empower both women entrepreneurs and investors (http://www.goldenseeds.com). Over thirty training modules are available on topics such as the risks and rewards of angel investing, structuring a deal, financial due diligence, and board membership. For successful women entrepreneurs, investing in and supporting other women entrepreneurs is one of the many ways they can give back. More examples and resources are provided in later chapters. This motivation to give back and support other women is particularly important, because, as we will demonstrate in this book, one of the major challenges for growth-oriented women entrepreneurs is the challenge of securing adequate financial capital to launch and grow their ventures. In light of that, we need those successful women entrepreneurs, the Sara Blakelys and the Oprah Winfreys of the world, to “pay it forward” by investing in the entrepreneurial dreams of others.

Financing Strategies for Growth-Oriented Women Entrepreneurs

As we have observed in this chapter, the profile of women entrepreneurs is changing, and changing in positive ways thanks to educational, workplace, social, and cultural shifts. Each of these has had the effect of opening the door to growth-oriented entrepreneurship a bit wider for women. As we have also shown, a growing number of factors are not only creating opportunities but also providing the motivation for women to pursue growth. One barrier that still remains, however, is the barrier of securing adequate financial capital to launch and grow a firm. Current research suggests that women entrepreneurs have largely leveled the playing field in terms of access to debt capital, although they continue to borrow smaller amounts than men (Coleman and Robb, 2009; Haynes and Haynes, 1999). A significant gap between women and men remains, however, when it comes to securing sources of equity capital in the form of angel investments, venture capital, or private equity (Brush, Carter, Gatewood, and Hart, 2004; Harrison and Mason, 2007; Robb, 2013). This is not necessarily a problem for smaller firms, which tend to rely on internal sources of capital and external debt in the form of bank loans. Nevertheless, accessing sufficient amounts of external equity capital is a major impediment for women entrepreneurs who launch growth-oriented firms. As we ride the “next wave” together, we will explore the financial challenges faced by growth-oriented women as well as the financial strategies that successful women have employed to overcome those challenges.

In addition to delivering a contemporary account of financing strategies from the entrepreneur’s perspective, we will address investor perspectives on financing. To date, most books on growth-oriented entrepreneurship have focused on the entrepreneur’s challenges and strategies but have ignored the investor side of the equation. Since growth-oriented firms typically require large amounts of external equity, the investor perspective is critical. We will address this gap by detailing the development of a new generation of women investors. Accordingly, we will discuss strategies for mobilizing, educating, and training this cohort of potential female investors, while also teaching women entrepreneurs how to effectively engage with these counterparts. In this sense, we see The Next Wave as a “must read” for the thousands of women who are contemplating growth-oriented entrepreneurship, as well as those women who have gained sufficient wealth to take a more active role in growth-oriented investing.

Organization of This Book

The format of The Next Wave is organized around the life cycle of a growth-oriented firm and the financial issues and challenges that emerge at each stage of the life cycle. In this introductory chapter, we have discussed motivations for growth and have profiled three highly successful growth-oriented women entrepreneurs. In Chapters 2 and 3, we provide a status report on growth-oriented women’s entrepreneurship, as we lay out some of the challenges that women face in trying to scale their companies. Chapters 4 and 5 focus on the financial challenges and strategies associated with nascent and early stage growth-oriented firms. Since the survival stage is a “make or break” point in the development of growth-oriented firms, we devote Chapters 6 and 7 to an exploration of the challenges that accompany that stage, as well as the financial strategies used by successful growth-oriented entrepreneurs to overcome them. We look at the emerging phenomenon of crowdfunding in Chapter 8, and how this strategy can be used not only for financing but also for product and price testing, market validation, and more. Chapter 9 focuses on how growth-oriented women entrepreneurs can achieve significant scale and scope. This, in turn, may lead to “harvesting value” in the form of an initial public offering, a process that we describe in Chapter 10. Most books on entrepreneurial finance would end with this particular “happy ending.” In our case, we see the harvest event not only as a happy ending, but as a happy beginning for the next stage for growth-oriented women entrepreneurs, the stage that involves their transition from entrepreneur to investor. We describe this transition, as well as its importance, in Chapters 11 and 12.

As we make this journey together, we will rely on both qualitative and quantitative data documenting the motivations, experience, and challenges faced by growth-oriented women as well as their financial strategies for growth. To this end, each chapter will incorporate the stories of “real world” growth-oriented entrepreneurs. In this introductory chapter, we have drawn upon secondary sources to highlight the experience of three very successful high-profile women entrepreneurs, Sara Blakely, Oprah Winfrey, and Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw. Going forward, however, we will share case studies based on interviews done with growth-oriented entrepreneurs at various stages of their firms’ life cycles. These case studies feature women who have employed a broad range of financial strategies in their pursuit of entrepreneurial growth. Similarly, the case studies provide examples of growth-oriented entrepreneurship across a broad range of industries.

We will also draw upon prior research in the areas of entrepreneurial finance and women’s entrepreneurship to identify the financial issues and challenges associated with firm growth. Finally, we will incorporate our own research using data from the Kauffman Firm Survey, a longitudinal dataset that collected data on more than four thousand U.S. firms launched in 2004, which were tracked over an eight-year period. The KFS is an invaluable resource in that it provides detailed information on owner characteristics and firm performance, as well as financial structure and strategies.

At the end of each chapter, we integrate findings from our entrepreneur interviews with those drawn from current and prior research to “close the loop” by summarizing the chapter’s key takeaways. Similarly, each chapter ends with a section titled “What Does This Mean for You?”, which is designed to help you, our readers, apply each chapter’s takeaways to your own entrepreneurial ventures and journeys.

As we begin this new voyage together, we embrace this opportunity to intertwine findings from the latest research and practice as they relate to the financing strategies of women entrepreneurs who have high-growth aspirations. As we have noted, the entrepreneurial landscape is changing rapidly, and changing in ways that will benefit women entrepreneurs. They are the “next wave,” and they are already having a profound effect on business, society, and our economy. These are truly exciting times for us and for them!

Closing the Loop

In this chapter, we have addressed the fundamental question of what motivates women entrepreneurs to grow their firms. In doing so, we have drawn upon the examples of three highly successful growth-oriented entrepreneurs, Sara Blakely, Oprah Winfrey, and Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw. In Sara’s case, she was motivated by an opportunity in the marketplace to develop a line of comfortable shapewear products that would increase women’s confidence in themselves while also allowing her to enjoy the financial rewards associated with launching a growth-oriented firm. Oprah Winfrey has also enjoyed these same financial rewards and is listed as one of the four hundred wealthiest individuals in the United States. At the same time, however, entrepreneurship has served as a pathway for Oprah to become a role model for millions of women and girls as well as a thought leader on a broad range of issues. Biogen founder Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw has used growth-oriented entrepreneurship as a means for making health care more accessible and affordable on a global scale. As we have seen, each of these remarkable entrepreneurs has been driven by a combination of factors that include the pursuit of an opportunity, financial gain, being recognized as a leader in her field, and making an impact that will improve the lives of countless others.

We have pointed out that, traditionally, women have launched very small firms for a variety of reasons. Although many of these firms are very successful, they do not create the same type of economic impact that larger firms are able to create, leading the Kauffman Foundation’s Lesa Mitchell to refer to women who are capable of launching growth-oriented firms as “our greatest under-utilized economic resource.” More recently, however, a new generation of women entrepreneurs is embracing both the challenges and the rewards associated with growth.

For these women, educational and workplace gains combined with changing cultural and societal factors have opened a door that was previously closed to many. In effect, these changes have made it much more possible for women who want to grow their firms to do so. In spite of this progress, the path of growth-oriented entrepreneurship is not an easy one. For women, in particular, there continue to be obstacles, some of which are structural and others attitudinal. One such barrier that has been especially intransigent is women’s ability to secure sufficient amounts of financial capital to launch and grow their firms. Prior research consistently shows that women start their firms with smaller amounts of financial capital than men and that they go on to raise smaller amounts of capital post-launch. These findings have serious implications not only for the growth of women-owned firms, but for their very survival. Our goal in The Next Wave is to take on this challenge by identifying and sharing the financial strategies that have helped women entrepreneurs grow their firms. We will do so through a combination of case studies featuring growth-oriented women entrepreneurs as well as through research using data from the Kauffman Firm Survey.

In addition to focusing on the growth potential of women entrepreneurs, The Next Wave will focus on the potential of women as investors. The same factors that are opening doors for growth-oriented entrepreneurs have also created opportunities for women to accumulate significant amounts of wealth in the form of career-generated earnings or the proceeds from their own entrepreneurial ventures. Just as women have been underrepresented in growth-oriented entrepreneurship, they have similarly been underrepresented as investors in entrepreneurial firms. In this book, we will explore ways for unlocking the unrealized potential of women capable of investing in growth-oriented firms, including those launched by other women. This perspective will allow us to address both the entrepreneur and the investor sides of the equation, creating a virtuous circle whereby successful women are able to help and support growth-oriented women entrepreneurs who will eventually be in a position to do the same for others.

What Does This Mean for You?

Although we often associate growth with high-tech firms such as Apple Computer, Google, and Facebook, the examples from this chapter illustrate that every industry has potential for high-growth firms. This is important, because women entrepreneurs are currently more heavily represented in the service, retail, and health care industries than they are in technology-related fields. This is changing, but the point is that women entrepreneurs have growth opportunities, no matter what industry their companies are in.

In The Next Wave, our goal is to provide those women entrepreneurs who are pursuing growth with an array of financial strategies that can help them achieve it. With that in mind, we leave you with the following thoughts as we conclude this first chapter:

If any of these questions strike a familiar chord, you have come to the right place. Using the stories of entrepreneurial women just like you, we will navigate the growth process from a firm’s earliest stages through to harvesting value and beyond with a focus on the financial strategies that work at each stage. Welcome aboard! It’s time to launch!

1. In 2013, of the top one hundred women on the Forbes list of most influential women, twenty-four were corporate CEOs that controlled $893 billion in annual revenues and sixteen founded their own companies, including two of the three new billionaires on the list, Tory Burch, founder of the Tory Burch line of clothing, and Spanx’s Sara Blakely. Five women in the field of technology also made the top twenty-five, including familiar names such as Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg (no. 6), Pepsi’s Indira Rometty (no. 12) and HP’s Meg Whitman (no. 15).

2. These “breadwinner moms” are made up of two very different groups: 5.1 million (37 percent) are married mothers who have a higher income than their husbands, and 8.6 million (63 percent) are single mothers.